|

http://www.jonimacfarlane.com/blog

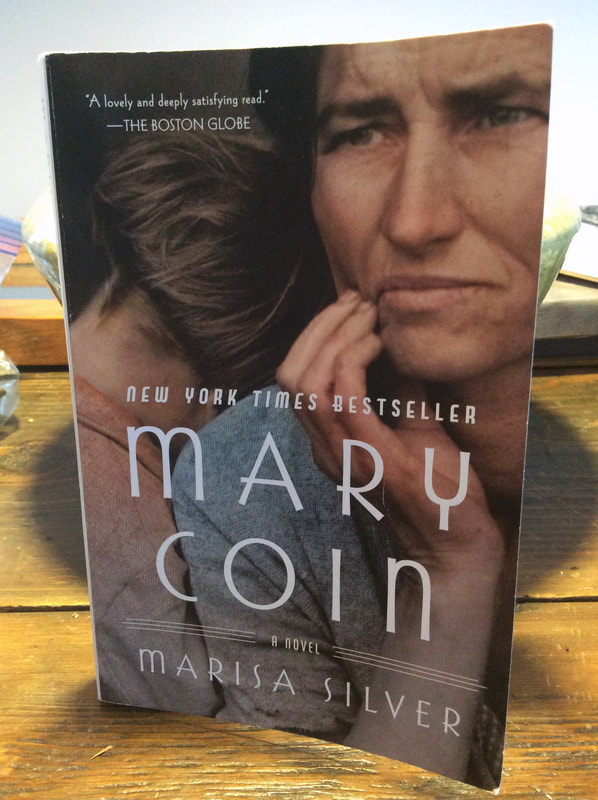

Well here we are, we’ve turned the corner and made it into 2021. So far, it’s shaping up to be a doozy. But there are good things on the horizon and so many great reads ahead of us, it’s hard not to get excited. My holiday season reading was wide and unpredictable - essays from a mixed race gay man, a fictionalized account of a young Anton Chekhov, a chilling suspense, and a collection of short stories. But Marisa Silver’s Mary Coin tugged at me like a child at her mother’s hem. After reading I knew I had to devote a blog post to it. Culturally, when people think of the Great Depression, John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath often comes to mind. It is deservedly cited as one of literature’s greatest achievements, capturing the gruelling poverty and unbearable struggle of a generation. Another cultural icon is a photograph: a close-up of a woman looking into the distance, two children at her side facing away from the camera, a baby in her arms. Migrant Mother became emblematic of those years. It gave a face to the plight of thousands of people who lived and laboured in the fields of California picking fruit. The photograph and photographer became famous but very little was known about the subject or how it came about. Who was she? How did she come to be sitting on the side of the road surrounded by her young children? What was her story? And why did the photographer stop at this particular woman? What was she hoping to capture and what did it mean to her to take this anonymous woman’s picture? Mary Coin is a fascinating fictionalized attempt to answer these questions. Based partly on true facts and partly on imagined, the narrative features the stories and voices of three people: Mary Coin, knocked down by life, but determined and pragmatic to the end, the photographer Vera, mired in her feelings of unworthiness, but strong enough to forge her own path, and Walker, a professor of cultural history, struggling to understand the life he has created and overwhelmed by his place in it. Each has a fascinating and utterly unadorned voice. Widowed with six children, Mary (whose real name was Florence Owen Thompson) winds up picking oranges in California in the mid-1930s. Resolutely, she looks ahead with a steely eye to the future. “Mary sustained the weight of sorrow that would descend on her freshly each morning she woke up and had to remind herself her husband was gone...[but] a larger grief was still out there, waiting to overtake her when she was not looking. She had to be careful.” Vera (the real photographer was Dorothea Lange), whose own marriage had ended, had a government contract documenting the plight of migrant workers. She looks back and wonders what made her stop at that particular woman. She questions her work, wondering if it’s delusional to think photographs capture life. “She had seen so much but understood so little.” Interspersed with these women’s lives, is Walker. In the present day, we watch him search to understand his deceased father, his guilt about his children, and his essential loneliness, through the lens of history. He wonders if he is really seeking the truth or if the history we choose to interpret is only a deception of something we can live with. Never maudlin, the story is told with a raw, emotional language, that left me breathless. This chance encounter of two women, documented in a photograph, only scratched the surface of their lives, but the reverberations imagined here will stay with me a very long time. Please don’t stop wearing your masks. Please get the vaccine when you can and talk to your friends and family to be sure they get it too. Above all, stay hopeful. In the meantime, happy reading! Joni

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed