|

http://www.jonimacfarlane.com/blog

Many years ago, I wrote a short story for a Calgary Herald contest and won third prize. Fame and glory awaited. In the meantime, I received a small cheque and was published in the Herald’s now-defunct Sunday magazine. Shortly after, a letter to the editor was submitted chastising the newspaper for printing a story that was not, in the reader’s opinion, fit for a family paper.

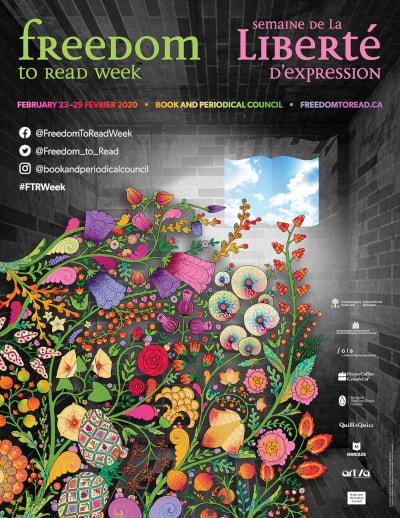

I was ecstatic. My story had elicited an emotional reaction, strong enough that someone wrote to complain. Even a negative reaction was better than no reaction. Luckily for me, the Herald was more interested in good stories than in protecting its readers’ moral values. I’ve always admired that. Last week was Freedom to Read week, an annual event that encourages us to think about and reaffirm our commitment to intellectual freedom. It’s an opportunity to think about how lucky we are in Canada that books and magazines with controversial themes are widely published and we can read whatever we like. Guaranteed under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, we have freedom of speech, freedom of expression, and protection from censorship. No one has the right to tell us what we can and can’t read. However outside your comfort level they may be, books can be written, published and read on any subject someone may be willing to print (digitally or otherwise). Of course, not every country is so fortunate and, even in our own backyard, there are times when the luxury of reading whatever you want isn’t always so. Libraries and schools are regularly asked to remove certain books and magazines from their shelves. It got me thinking: what books are often challenged and why? Here’s a rundown of Canadian books most targeted. The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood Released in 1985, The Handmaid’s Tale’s “profane language, anti-Christian overtones, violence and sexual degradation” have seen this book widely challenged, mainly by parents of high school aged children. As the book deals expressly with themes of repression and censorship, the irony of such challenges is not worth mentioning. Underground to Canada by Barbara Smucker A historical novel for young readers that tells the story of escaped slaves from the U.S. who travelled into Canada through the underground railroad. In 2002, there was a motion to remove this work from classrooms in a southwestern school board in Nova Scotia, with objections to the depictions of black people in what they deemed, an anti-racist novel. The school board ultimately rejected this request. A Jest of God by Margaret Laurence In 1978, a school trustee in Etobicoke, Ontario tried, but failed, to remove this novel from high school English classes. The trustee objected to the portrayal of teachers “who had sexual intercourse time and time again, out of wedlock”. He said the novel would diminish the authority of teachers in students’ eyes. Such is My Beloved by Morley Callaghan Set in the 1930s, this novel tells the story of a young Roman Catholic priest who tries to persuade two women to abandon their lives as prostitutes. In 1972, two Christian ministers tried to get this novel removed from a high school in Huntsville, Ontario based on the depiction of prostitution and the use of “strong language”. Barometer Rising by Hugh Maclennan A story of family conflict and romance set in Halifax during WW1. At a convention in 1960, members of the Manitoba School Trustees Association voted unanimously to ask the provinces’ department of education to remove this novel from the high school curriculum. Trustees objected to the “vulgarity and language used” though later admitted to not having read the novel. The Wars by Timothy Findley Also set during WW1, the novel features not only a scene depicting a sexual encounter between two men, but also a rape which is perpetrated against the protagonist soldier. Calling it “depraved” parents on two occasions called for this Governor General Award-winning novel to be removed from all classrooms. In both instances, the school board upheld the use of the book in secondary school curriculum. Lives of Girls and Women by Alice Munro Lives of Girls and Women chronicles a young girl’s experience growing up in rural Ontario as she grapples with the crises that accompany her journey into womanhood. In the late 70s, this novel was removed from an Ontario reading list as the principal called into question the suitability based on “explicit language”. The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler Duddy, a third-generation member of a Jewish immigrant family in Montreal, dreams and lives large. Amoral, ruthless and scheming, Duddy is one of literature’s most magnetic anti-heroes. Parents demanded the removal of this novel from high school reading lists, objecting to its “vulgarity, sexual expression and sexual innuendoes”. The Diviners by Margaret Laurence Part of a five-book series, The Diviners tells the story of Morag Gunn, a writer and single mother. Letters written in Canadian newspapers at the time opined that “the educators in Peterborough would be deficient in their duties if regard were not had for those whose values and sensibilities might be offended by profanity and explicit sex as found in Mrs. Laurence’s “work of art”. Fundamentalist Christians deemed the book “obscene” and several schools complied. Hold Fast by Kevin Major Two brothers, Michael and Brent, are uprooted from their tight-knit Newfoundland community and eventually separated when their parents are killed in a car accident. Although winning the Governor General’s Literary Award for English-language children’s literature, it was banned for containing foul language, mild sexual content and –egad – bad grammar. When Everything Feels like the Movies by Raziel Reid An edgy and extravagant YA novel about a glamourous boy named Jude, the book examines the violence endured by LGBTQ people. It was winner of the 2014 Governor General’s Award for Children’s Literature, but was decried as a “values-void novel” by a National Post columnist. Shortly after, a group of concerned parents, YA authors, and teachers started an online petition to revoke the award, citing the book’s “offensive and inappropriate content”. This is just a smattering of books that people have called to be banned. Looking through literature’s most widely censured books, I’m proud to say I’ve read quite a few. The ability to read what you want is one of our most crucial freedoms, allowing us to view the larger world with all its perspectives – the good, the bad and most importantly, the ugly. Don’t take it for granted. Until next time, happy reading! Joni

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed